Daniel Reeve is an artist and calligrapher who created the maps and calligraphy for the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit films, including the contract from The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. You can read our analysis of the contract in this series of posts. After a commenter pointed us in his direction we contacted Mr. Reeve, and he agreed to an interview.

Law and the Multiverse: You created much of the calligraphy and maps for The Lord of the Rings films and now The Hobbit films. How did that working relationship come about?

Daniel Reeve: I had read Tolkien’s books as a teenager, and had tinkered with calligraphy – including elvish calligraphy and runes – ever since then, so when I heard that The Lord of the Rings was being made into a film, practically on my doorstep, the opportunity was too good to miss. I submitted some samples of elvish calligraphy to the film company; they phoned me immediately, and the next thing I knew, I had the job of doing all the calligraphy for the films. This immediately expanded to include maps and other graphics; and expanded even more in The Hobbit, where I create much of the artwork seen in the films, as well as the usual calligraphy, books, scrolls, parchment, inscriptions, maps, etc.

LatM: The contract in the book is quite short, just 44 words for the essential terms. How did that become the multi-page contract in the movie?

DR: I set about creating a simple document using text taken directly from Tolkien’s book, and using a dwarvish-looking calligraphic style that vaguely resembled the runes which they use for most purposes. This first version was about A4 size (though not the shape of A4 – we avoided that distinctive width/height ratio in all documents, so that Middle-earth wouldn’t look like something from our own era.)

The feedback from PJ & co. was that they wanted more text. Add a clause or two. Make it longer.

So I prepared version 2, and I also started playing with possible signatures to be added at the bottom.

The feedback: “More text, please; let’s try two pages. And could we have the signatures more ‘Elizabethan’-looking.” I duly created version 3, as well as a raft of possible signatures for Balin, Glóin, Thorin Oakenshield, and of course Bilbo Baggins.

They selected a signature for each character, but the main message coming back continued to be “More text!”

I drew up version 4….

“More text! Complicated, long-winded clauses! Fine print!”

I added finer print to all the available gaps in version 4, but I could see where this was heading….

“More text! Finer print!”

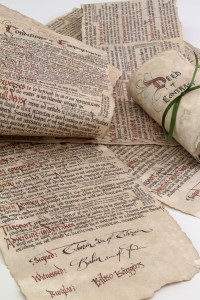

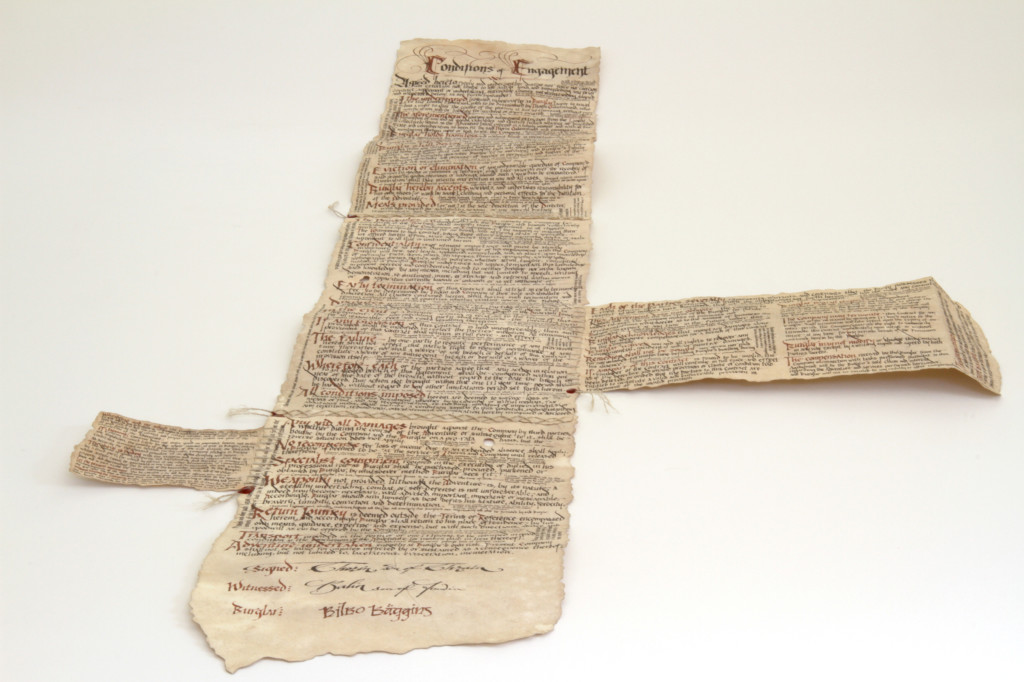

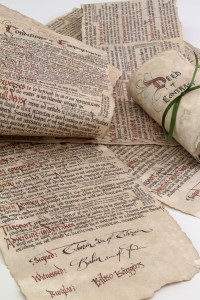

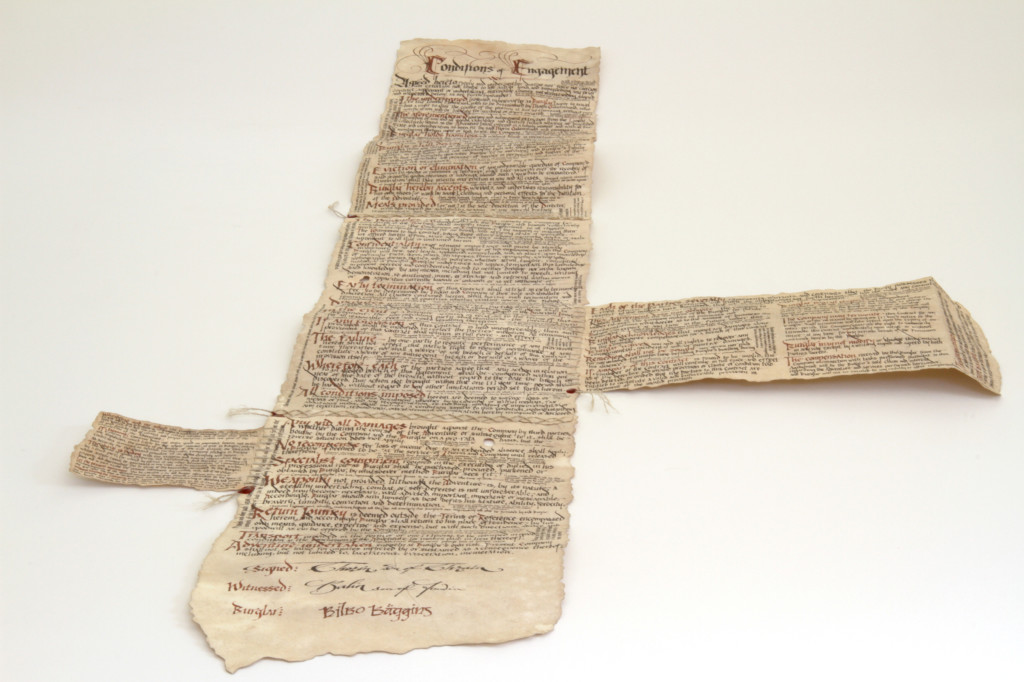

Right. Okay. You want lots of text, I’ll give you lots of text! We decided it should be a long scroll – so long that several pieces of parchment would have to be stitched together, in order to be able to fit all the clauses in. And then numerous addenda, riders, extra clauses could be added as extensions to the sides, folding out to be read. And the Contract would be written in a different style, quite a dense calligraphy, but not as hard to read as blackletter. I devised a writing style, and experimented with widths and lengths of parchment, and arrangements for the side additions.

I invented all kinds of original weird and wonderful clauses and conditions; then scoured every contract and agreement I could lay my hands on (including my own contract with the film-makers) and borrowed and re-worded and invented some more, until eventually I had filled the parchments. In fact there were two more side bits that were eventually discarded – but certainly the final document was wordy enough to bamboozle, flummox and overwhelm any poor hobbit or other potential burglar.

The contract from The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey

LatM: While some parts of the contract appear to be drawn from a modern contract, other parts are clearly original. Did you consult with an attorney in writing the contract or go it alone? Did you look at any old contracts for inspiration or wording? Was the lengthy and lop-sided nature of the contract a little inside joke about the equally lengthy and lop-sided nature of film contracts?

DR: The Contract had to include the lines from the film script about “lacerations, evisceration, incineration”; but apart from that, I created the entire contract without consultation. From a film-making point of view, the actual wording was unimportant, the whole thing being basically a visual gag about the ridiculous length and complexity of the contract, and the fact that a contract was needed at all! Knowing how it was likely to be shot, you might think that I could just as easily have written greeking text; lorem ipsum, etc – there was certainly no need to resort to (or pay for!) consulting an attorney, let alone the time factor. But as with all things in these films, authenticity and attention to detail are called for, and pay off in the end. Besides, you never know whether the director will decide to shoot a close-up of this or that on the day. And it’s easier – and more satisfying by far – to write stuff that actually makes sense.

I naturally started with the essence of Tolkien’s original – where Bilbo’s entitlement to one fourteenth of the profits are promised, funeral arrangements and travelling expenses are provided – and expanded it in the same vein. Both the book and the film script called for the comical aspect, so I invented all sorts of absurd clauses, being as original as possible, and wrapping them in as much legalese as I could think of. Why say in one word what you can expand to three or four?! So the in-jokes came thick and fast, including reference to my own contract with the film company, and re-wording the typical standard clauses and boilerplate from real contracts, both modern and old.

It’s lengthy, lop-sided, repetitive; and – as in real contracts, it seems to me – the devil is in the detail. Always read the fine print!

LatM: How many original props did you have to create for the movie? Did you get to keep any?

DR: I have created many, many original movie props and set dressings for these films; but you never get to keep anything, of course. Everything belongs to the film companies, and often has a future in exhibitions of film paraphernalia. And in the case of the Contract, as merchandise for fans.

LatM: To me, the long contract spilling out page after page with its multiple fold-outs is a comic scene, but it also says something about dwarven culture, or at least about the Company, namely that they want everything properly specified and well ordered. How else did you try to capture the dwarves’ personality in the contract?

DR: The lettering style has a few rune-inspired features. And there’s a kind of grasping, greedy aspect not only in the content of the Contract, but also in the way that every available space is used, filled with smaller and smaller writing, rather than using more of that expensive parchment.

LatM: In your mind, which member of the Company actually wrote the contract (i.e. who put pen to paper)?

DR: Balin is the scribe of the group, and the one familiar with legal matters. The film script writers assigned different characteristics to each of the dwarves, to help make them easier to identify; so the Contract is definitely written by Balin.

LatM: The contract has a unique style. It’s very comprehensive, but it’s also sort of scattered, with a lot of afterthoughts and marginalia. How did you develop it? At least one commenter has suggested that the marginal notes and addenda may reflect that the contract was written by a committee of 13. Do you see some parts as coming from different members of the Company (e.g. the part about fire safety officers coming from Glóin and Óin, the best fire makers in the Company)?

DR: I certainly thought of this as being a collaborative effort, from the various members of the Company. Balin – partly in consultation with Thorin – would have first set down all the main clauses of the Contract. But they and the others would realise they’d left out this or that, and add it later. And as it became more complex, they would forget that some things were already set forth, and would add them again – this explains some of the repetitions.

This haphazard, scattered construction, with the afterthoughts and marginalia, also reflects how it was really written! Because I would realise that I still needed more text to fill the thing up, so I would put my thinking cap on and come up with additional clauses.

***

Thanks again to Daniel for a great interview! For the collectors among us, two versions of the contract are available for purchase: a hand-made replica from Weta and a less detailed version from the Noble Collection.

Our new book, The Law of Superheroes, is now available! Order your copy today!

Our new book, The Law of Superheroes, is now available! Order your copy today!